This term at the University of Oldenburg, Stephan Kornmesser and I are teaching a course for master’s students who had no previous contact with x phi.1 We decided to try a hands-on approach rather than just discussing results, debates, and ideas from the field. For this purpose, we divided the course into two parts. In the first half, loosely based on Kornmesser et al. (forthcoming), we introduced some basics of experimental design and statistical analysis. Also, as a paradigmatic example of an early x phi study, we read Knobe (2003). In my opinion, this paper has the advantage of being both short and accessible; the experimental design is simple and the data collected (primarily the nominal yes-or-no responses) can be analyzed quite straightforwardly.

Thereafter, the course was divided into three groups,2 and students were instructed to replicate Knobe’s first study step by step. First, we reconstructed the questionnaire, using a German translation of the vignette (taken from Knobe 2014). Everyone probably knows the vignette, but to refresh your memory, here is the original once again (variations between Harm and Help Condition are indicated by square brackets):

The vice-president of a company went to the chairman of the board and said, “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits, but [and] it will also harm [help] the environment.”

The chairman of the board answered, “I don’t care at all about harming [helping] the environment. I just want to make as much profit as I can. Let’s start the new program.”

They started the new program. Sure enough, the environment was harmed [helped].

Knobe (2003, 190)

Afterwards, students used the questionnaire to ask people on campus whether the chairman brought about the side effect intentionally. Finally, we calculated and interpreted χ2 tests for each group. To foster an understanding of how the χ2 test actually works, we calculated them by hand one step at a time instead of using software.

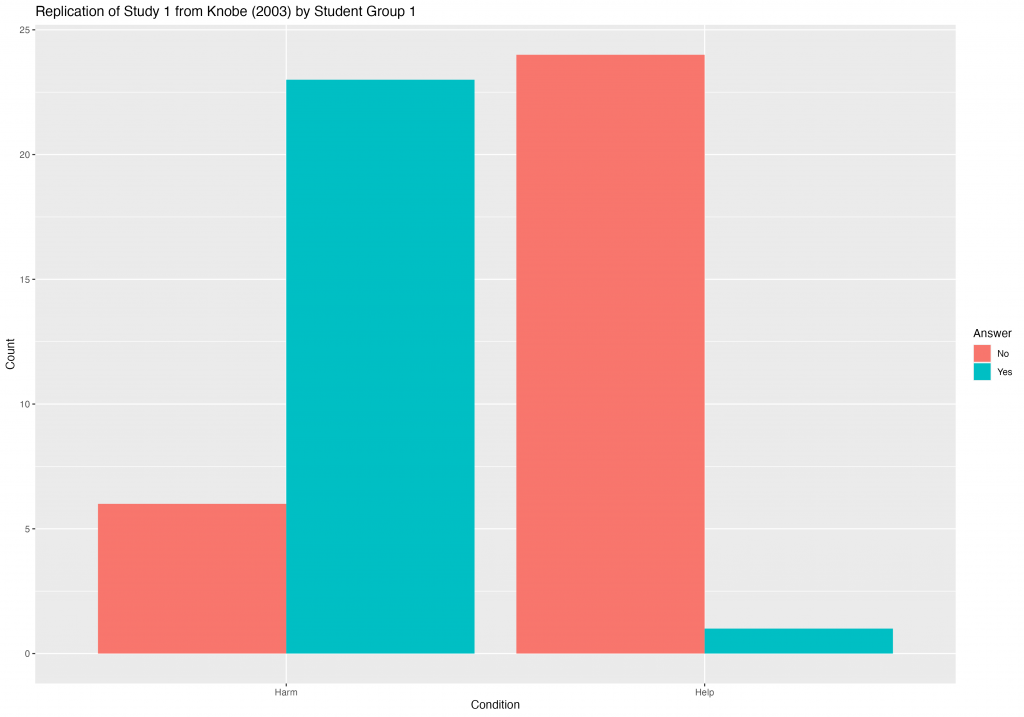

As can be seen in the picture below, showing the results from Group 1, Knobe’s original findings were perfectly replicated.3 In the Harm Condition, most subjects said that the chairman brought about the side effect intentionally, while in the Help Condition, most subjects said that he did not.4

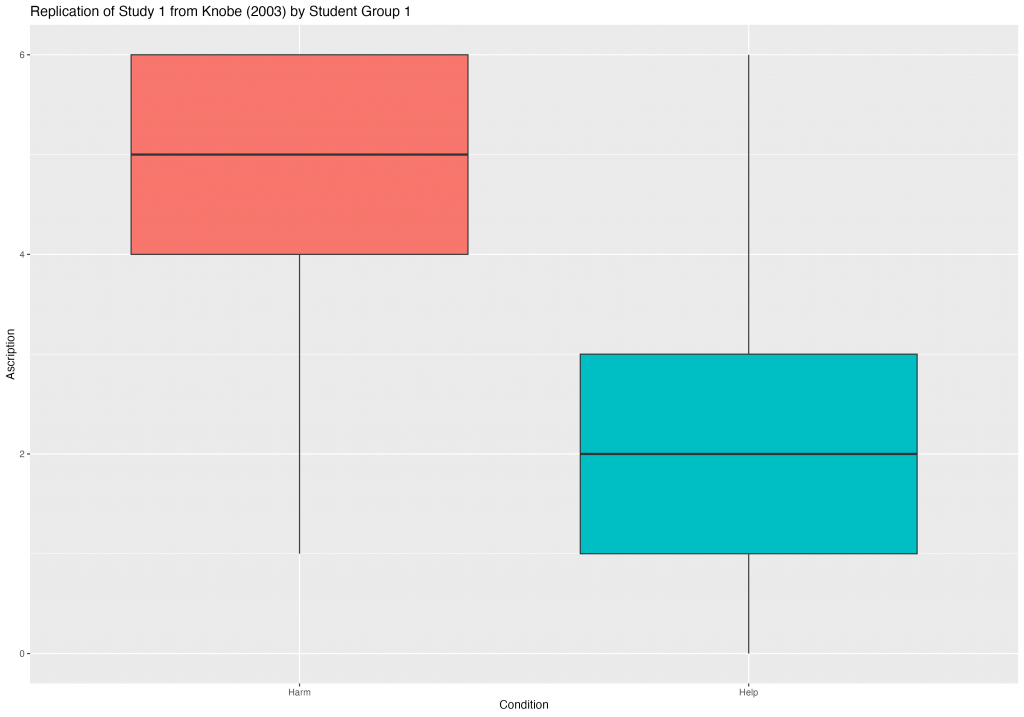

As did Knobe (2003), people were also asked how much praise or blame the chairman deserves. Using the results from Group 1 again as an example, shown in the picture below, the mean of ascribed blame was 4.90 (SD = 1.26), while the mean of ascribed praise was 2.32 (SD = 1.63), which also fits in very well with Knobe’s results.5

Where do we go from here? In the second half of our course, the three groups are encouraged to develop their own research questions based on their philosophical interests. They will learn how to design an online survey and set one up themselves. Luckily, we have got a grant for research-based learning instructional projects from the university’s initiative forschen@studium,6 which will be used to recruit subjects from an online panel provider. Hence, learning panel integration will also be on our schedule. This is followed by guided data analysis and interpretation. Finally, the groups present their results to each other and document them in term papers. This means that, in the end, an entire research process is experienced.

Literature

De Cruz, Helen (2019): “Unconventional Teaching Ideas That Work. Teaching Experimental Philosophy to Undergraduate Students”, The Philosophers’ Cocoon, https://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2019/02/unconventional-teaching-ideas-that-work-teaching-experimental-philosophy-to-undergraduate-students-h.html.

Kornmesser, Stephan, Alexander Max Bauer, Mark Alfano, Aurélien Allard, Lucien Baumgartner, Florian Cova, Paul Engelhardt, Eugen Fischer, Henrike Meyer, Kevin Reuter, Justin Sytsma, Kyle Thompson, and Marc Wyszynski (forthcoming): Experimental Philosophy for Beginners. A Gentle Introduction to Methods and Tools. Cham: Springer.

Knobe, Joshua (2003): “Intentional Action and Side Effects in Ordinary Language”, Analysis 63 (3), 190–194.

Knobe, Joshua (2014): “Absichtliches Handeln und Nebeneffekte in der Alltagssprache”. Translated by Jürgen Schröder. In: Thomas Grundmann, Joachim Horvath, and Jens Kipper (eds.): Die Experimentelle Philosophie in der Diskussion. Berlin: Suhrkamp. 96–101.

Endnotes

- If you are interested in teaching x phi to beginners, you should also take a look at De Cruz (2019). In her blog post, she describes a teaching approach to third-year undergraduates at Oxford Brookes University. ↩︎

- Of course, the great students of our course deserve credit! Group 1: Johannes Bavendiek, Marvin Jonas Laesecke, and Aileen Wiechmann; Group 2: Rebecca Kratzer, Frederike Lüttich, and Jule Rüterbories; Group 3: Bastian Göbbels, Finn Ove Gronotte, Marina Hinkel, and Riduan Schwarz. ↩︎

- Data and materials can be found at https://github.com/alephmembeth/course-x-phi-2024. ↩︎

- χ2(1, 54) = 27.865, p < 0.001. For comparison: Knobe (2003, 192) reports χ2(1, 78) = 27.2, p < 0.001. ↩︎

- t(54) = 6.43, p < 0.001. For comparison: Knobe (2003, 193) reports – pooled for both of his studies – a mean of 4.8 in the harm condition and of 1.4 in the help condition; t(120) = 8.4, p < 0.001. ↩︎

- See https://uol.de/en/forschen-at-studium. ↩︎