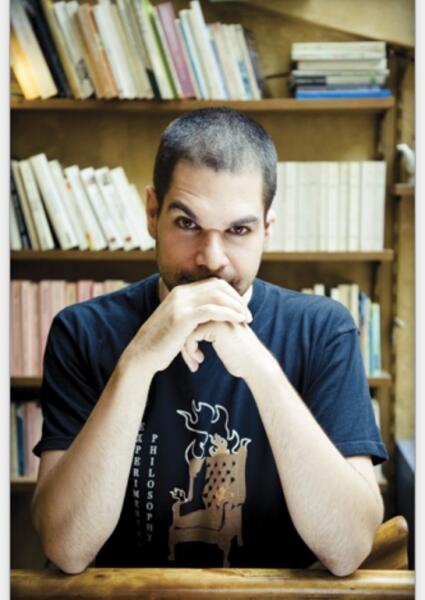

In our “Faces of X-Phi” series, experimental philosophers from all around the globe answer nine questions about the past, present, and future of themselves and the field. Who would you like to see here in the future? Just leave a suggestion in the comments! Today, we present Josh Knobe.

The Past

(1) How did you get into philosophy in the first place?

I was always obsessed with philosophy, but at least at first, I had a lot of misgivings about going into academia. Back when I was an undergrad, I had a sense that academic philosophy was too much a matter of playing some little game designed to display one’s own cleverness and not enough a matter of genuinely trying to get to the bottom of things.

So after I graduated from undergrad, I left the world of academia and took a bunch of random jobs. I had a job working with homeless people. I spent some time translating documents from French and German for a computer company. I was writing software that helped low-income people get housing. For a little while, I was teaching English in a small town in Mexico.

But that whole time, I was still writing philosophy. I would write philosophy papers on nights and weekends. Then, when I thought a paper was completely done, I would put it in my desk drawer and never show it to anyone again. (Needless to say, all of these philosophy papers were awful.)

After four years of that, I started to feel that my life was going nowhere, and I applied to grad school in philosophy.

(2) And how did you end up doing experimental philosophy?

Even when I first arrived in grad school, I was running experimental studies. I was working with a professor in the psych department and putting together the papers for psychology journals. But fundamentally, I saw that whole thing as a hobby – just a little thing I was doing on the side.

My main focus at the time was on work that was more in the Continental tradition. I was obsessed with Kierkegaard, Sartre, Marx. My advisor was the Nietzsche scholar Alexander Nehamas.

Then, after a few years, I had something of an existential crisis. I started to feel that this work I had been doing in the Continental tradition was not the best way to answer the questions that were troubling me. And I started to think that maybe work using experimental methods – the very thing I had seen as just a hobby – might actually be a better way of pursuing those questions.

(3) Which teachers or authors have influenced you the most on your philosophy journey – and how?

Of course, all of us have been deeply influenced by our teachers and by various great figures from the history of philosophy, but if I think about it honestly, I would have to say that I have been much more influenced by my students and by other philosophers who are more junior than I am. Looking at the generation of philosophers who are now in their 20s and 30s, I feel like they have gone beyond my generation in so many important respects, and my whole approach to philosophy has been shaped by their contributions.

The Present

(4) Why do you consider experimental philosophy in its present form important?

As you probably know, there is a huge literature about this question already – tons of papers exploring metaphilosophical questions about what experimental philosophy is and whether it can shed light on important philosophical issues. But in my view, this entire literature has gotten off on the wrong foot. It isn’t even grappling with the questions that are most relevant here.

Just to start off with, what do experimental philosophers actually do day to day? In the first instance, what they do is to explore questions about how human beings think and feel. If you just pick out an experimental philosophy paper at random and start reading it, you will find a whole lot of evidence and arguments concerning questions about what is going on in human beings’ minds.

Now, what you see in the existing metaphilosophical literature is often an assumption that questions about human beings couldn’t possibly be philosophically relevant just themselves. So the thought is that if you want to understand what is philosophically important here, we have to show that facts about human beings can help us address some other question – a question that is not itself about human beings. Usually, the focus is on arguments of the form: Learning how people think about X can tell us about the true nature of X (e.g., learning how people think about causation can tell us about the true nature of causation). Then the assumption is that the key issue we need to grapple with as we explore the importance of experimental philosophy is whether or not arguments of this form can be made to work.

But this whole way of framing the issue is wrong from the beginning. If you want to understand what is so deep and important about experimental philosophy, you’ve got to actually care about questions concerning human beings. Most of this research is about exactly what it seems to be about. It’s about human beings, and how they think and feel. So if you want to understand why it is philosophically significant, you have to at least be talking about the potential philosophical significance of questions about human beings.

This point is so simple and straightforward that it almost feels like it should go without saying. Research in experimental philosophy of language is fundamentally about human languages, and if you don’t care about contingent facts about human beings and the languages they speak, you will never be able to understand what is supposed to be important about it. Experimental philosophy of law is about human systems of law, and if you think the only important questions in philosophy of law are about, say, the metaphysics of law, you will never understand why people are running all of these experimental studies.

Of course, we all know that some philosophers think contingent facts about human beings have no deeper philosophical significance. We can easily imagine the philosopher who says: “I think that there is no philosophical significance in itself to the study of how human languages actually work. Given that, please try explaining to me why your research in experimental philosophy of language is supposed to be valuable.” But in responding to such a person, we should not start out by conceding that this conception of philosophy might be correct. What we should be doing is arguing against precisely this conception.

(5) Do you have any critical points to make about experimental philosophy in its current state?

When it comes to experimental methods, there has been such a huge improvement over time. I’m really excited about all the reforms that have been introduced in recent years, but there is plenty to criticize about the way we did things in the early years of experimental philosophy.

As you may know, research methods in experimental philosophy were completely transformed by the replication crisis. The field has introduced a whole host of reforms that have allowed us to create more replicable research (larger sample sizes, pre-registration, open data, open code, etc.). The result has been a radical change in the whole character of the field. These days, it feels like there is much less interest in trying to put together flashy or counterintuitive findings and much more interest in just getting things right.

In the early years of experimental philosophy, before all these reforms, I think we were going wrong in some pretty fundamental ways. There was just way too much emphasis on getting results that would be “fun” or “exciting” and way too little on finding the right answer. The inevitable outcome was a whole bunch of results that failed to replicate.

More recent experimental philosophy is doing all the right things to avoid the bad practices we used at that time, but we need to do more on one specific front. There are still too many papers citing studies from that early time that have failed to replicate. If we are getting evidence that something doesn’t actually happen, we need to stop thinking about the philosophical implications of it happening and start thinking about the implications of the fact that it doesn’t happen. (As a small step in that direction, I put together a page with information about recent results that refute claims from my own previous papers.)

(6) Which philosophical tradition, group, or individual do you think is most underrated by present-day philosophy?

Traditionally, I think a whole style or approach to philosophy was tragically underrated. Things are getting better on that front, but I worry that we haven’t yet gone far enough in changing our view about this style of philosophy.

A number of decades ago, there was a clear sense that your goal as a philosopher should be to articulate a big new philosophical view and then argue that everyone else is wrong and your new view is right. So there was a widespread understanding that you were supposed to have some paper where you say: “In this paper, I boldly introduce View X.” Then, over the course of the next few decades, you were supposed to keep saying that View X was right and defending it against all objections. Let’s refer to philosophers who do this as “View X-ers.”

The View X-ers always get a lot of attention, and they can sometimes manage to upstage the philosophers engaged in another, very different form of inquiry. The most noticeable fact about these other philosophers is that they are curious about philosophical questions. They are thinking about the big issues, but they aren’t wedded to any specific view about those issues. Instead, they are focused primarily on trying to think carefully about the evidence and what it suggests about the various different views. We can refer to these philosophers as the “Curious-ers.”

Traditionally, I think the Curious-ers were completely underrated. They did lots of fantastic work, but all the attention got sucked up by the View X-ers. Things are clearly beginning to change on that dimension – but we still have not gone far enough. We need even more love for the Curious-ers!

The Future

(7) How do you think philosophy as a whole will develop in the future?

Well, it’s always a little bit hard to predict the future, but it’s easy to see what direction philosophy is going in right now, so let’s start with that.

When I first joined the field, Anglo-American philosophy was very dominated by certain specific approaches, and every other approach was seen as marginal or peripheral. Work on certain issues in metaphysics was completely dominated by a tradition associated with Kripke and Lewis. Work in political philosophy was completely dominated by a tradition associated with Rawls. And so on.

At this point, twenty years later, all of that has changed. In so many different ways, the influence of that formerly-dominant approach is receding, and all sorts of other approaches are rising in importance. It’s not that any single other approach has come to dominate everything. Rather, it’s that the previously dominant approach is becoming ever less prominent, and in its place, we see a flowering of all sorts of new research programs.

This change in the discipline of philosophy more broadly has led to a corresponding change within experimental philosophy. If you look back at the experimental philosophy that was published in the early 2000s, it’s easy to see that a lot of it is aimed at engaging with the traditions that were so dominant at that time (e.g., using experimental studies to argue against ideas from those specific traditions), but since then, things have changed radically. It’s not so much that recent work offers a different view about those same old questions; it’s more that people’s interests have broadened in so many ways, and people are now exploring all sorts of new issues that are almost completely unrelated to what philosophers were so focused on back then.

If you look at what is happening in philosophy of language these days, you see a massive decline of interest in the more metaphysics-adjacent questions that were so dominant in the 20th century and an embrace of a huge array of new questions coming out of linguistics. Experimental philosophy of language has very much gone in this same direction. These days, you can see a wealth of new research coming out about all sorts of different detailed, linguistic questions (generics, presupposition projection, epistemic modals, thematic roles, lexical causatives, etc.). And the same applies elsewhere. Philosophy of law used to be dominated by a relatively narrow range of questions in general jurisprudence, but in recent years, we see an explosion of new research about all sorts of other questions. Experimental philosophy of law shows that same change. Recent experimental work has looked at the concept of consent, the concept of the reasonable person – a whole array of exciting empirical questions.

(8) What do you wish for the future of experimental philosophy?

As a way into this question, let’s start with an analogy. Consider what we might wish for the future of scholarship in non-Western philosophy. I think that if we reflect on this question, we can get some helpful insight into what we should want for the future of experimental philosophy.

When American philosophers first turn to non-Western philosophy, they sometimes start with a preconceived view about what the important philosophical questions are (roughly, the ones from Western philosophy) and then ask how non-Western philosophy can shed light on those questions. What a terrible idea! Clearly, a better approach would be to pick up some non-Western texts and then look with an open mind at what philosophical insights we can get by exploring those texts. But of course, this takes work. If you are trained in Western philosophy, the first things you think of are questions from Western philosophy, and it can be hard to learn to think differently.

I see experimental philosophy in the same way. When people first start doing experimental philosophy, the obvious first approach is to keep working away on a list of preconceived questions borrowed from non-experimental philosophy. In some cases, people even proceed by just literally taking thought experiments from the non-experimental literature and running experiments using those very thought experiments. Ultimately, it seems unlikely that this will be the best approach. The best approach, I think, is to look at the empirical phenomena and try to think about what is most philosophically important in them.

Of course, this takes work, and if you are trained in non-experimental philosophy, it might be quite difficult at first, but I hope we can keep going even farther in that direction.

(9) Do you have any interesting upcoming projects?

These days, I am working on a bunch of unrelated projects. Here are two that might be worth mentioning:

(1) Matthias Uhl and I are working on a project about the idea that people see certain sorts of environments as the natural environments for human beings. Looking around ourselves, we see plenty of people living in cities, working for corporations, hunched over their laptops as they scroll pictures of acquaintances on Instagram… but people seem to think that this is not the natural environment for a human being to live in. Instead, the natural environment might be something like: walking in a forest while talking in person with a close friend.

What we find is that people attach a special significance to whatever you do when you are in this natural environment. If you behave one way while you are at the office hunched over your laptop but you act a very different way when you are taking a walk in the forest, people think that the way you behave when you are in the forest is more reflective of your true self.

(2) Linas Nasvytis, Fiery Cushman, and I are working on a project about which possibilities naturally come to people’s minds. Suppose you try to imagine something a person could have for lunch. There is no right or wrong answer here; just think of whichever lunch first comes to mind. When people try to do this, they often find that the first thing that comes to mind is something that they see as good. This fact seems like it might reveal something fundamental about people’s representations of categories.

We put together a neural net that represents categories in a way that shows this very same effect. The neural net samples objects from a category, and when it does this, it tends to sample objects that it regards as good. Comparing this computational model to data from human cognition, we are getting at least some initial indication that it might be on the right track.

2 thoughts on “Faces of X-Phi: Joshua Knobe”