This text was first published at xphiblog.com on June 22, 2021. It has been slightly updated.

I still remember how I sat on the porch last year, somewhen around April, reading Jonathan’s and Justin’s “Actual Causation and Compositionality” (Livengood and Sytsma 2020) for an upcoming session of X-Phi Under Quarantine, when suddenly – halfway through it – this idea struck me: There is something odd about the way subjects were asked by Jonathan and Justin, I thought.

But first things first. For those of you unfamiliar with the paper, I will give you a little rundown. Jonathan and Justin argue that theories of actual causation often endorse the Compositionality Constraint of Actual Causation (CCAC): For a series of individual events – say, c, d, and e – the CCAC states that if c caused e, then it did so either directly or it did so indirectly via at least one intermediary d. This intermediary then is itself an effect of c and a cause of e.

The CCAC’s validity does not solely rest upon experts’ intuitions. With the Folk Attribution Desideratum (FAD) (Livengood, Sytsma, and Rose 2017), it can be demanded “that what a theory of actual causation says about concrete, everyday cases [has to] accord with ordinary causal attributions” (Livengood and Sytsma 2020, 48).

Now, research has already shown that causal attributions can be influenced by normative judgements. This gives reasonable doubt that ordinary causal attributions accord with concrete cases. Jonathan and Justin hypothesize that, thus, “ordinary causal attributions will tend to violate the compositionality constraint for cases in which someone or something is responsible for an effect by way of an intermediary that does not share in the responsibility” (Livengood and Sytsma 2020, 48). To investigate whether this was the case, they conducted a series of vignette studies. One of them, the Revolver Case (RC), introduces subjects to the following story:

Trent has decided to kill his father, Brad. He aims his loaded revolver at Brad and pulls the trigger, releasing the hammer. The hammer strikes the cartridge, igniting the gun powder. The gun powder explodes, driving the bullet from the gun. The bullet hits Brad in the head. He dies instantly.

(Livengood and Sytsma 2020, 59)

After being introduced to this vignette, subjects had to state their agreement or disagreement with the four statements (1) “Trent caused Brad’s death”, (2)“The hammer caused Brad’s death”, (3) “The gun powder caused Brad’s death”, and (4) “The bullet caused Brad’s death” on a seven-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

Now, in case the causal attributions of laypeople would comply with the CCAC, subjects should agree to all statements of the RC: Not only was Brad’s death caused by Trent, but also by the hammer, the gun powder, and the bullet.

Here comes the first twist: In this study (and the remaining studies reported in their paper), subjects tended to rate statements about intermediaries as rather low. In the RC, responses indicate that Trent caused Brad’s death, while the hammer and the gun powder did not. Hence, the CCAC is clearly violated and does not meet the FAD.

Now, back to the beginning: What struck me as odd here was that there are a whole lot of statements about causation to be made from the vignettes used. But every time, Jonathan and Justin picked out only a small handful of them.

Take for example the RV, above. We can easily split the vignette up into eight events:

- Event A: “pulling the trigger”

- Event B: “releasing the hammer”

- Event C: “striking the cartridge”

- Event D: “igniting the gun powder”

- Event E: “the gun powder exploding”

- Event F: “driving the bullet from the gun”

- Event G: “the bullet hitting Brad in the head”

- Event H: “the death of Brad”

Next, we can combine those events to statements of the form “X caused Y”. Including all reasonable combinations of events to be made therefrom, this results in a total of 28 different items, including statements like, e.g., “Pulling the trigger caused the release of the hammer”, “Striking the cartridge caused the ignition of the gun powder”, or “The bullet being driven from the gun caused the bullet to hit Brad in the head”.

This is exactly what Jan Romann and I did in a small-scale study: First, subjects were presented the RV. Then, they were shown the 28 causal statements (in an ordered sequence). As in the original study, subjects had to state their agreement on a seven-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

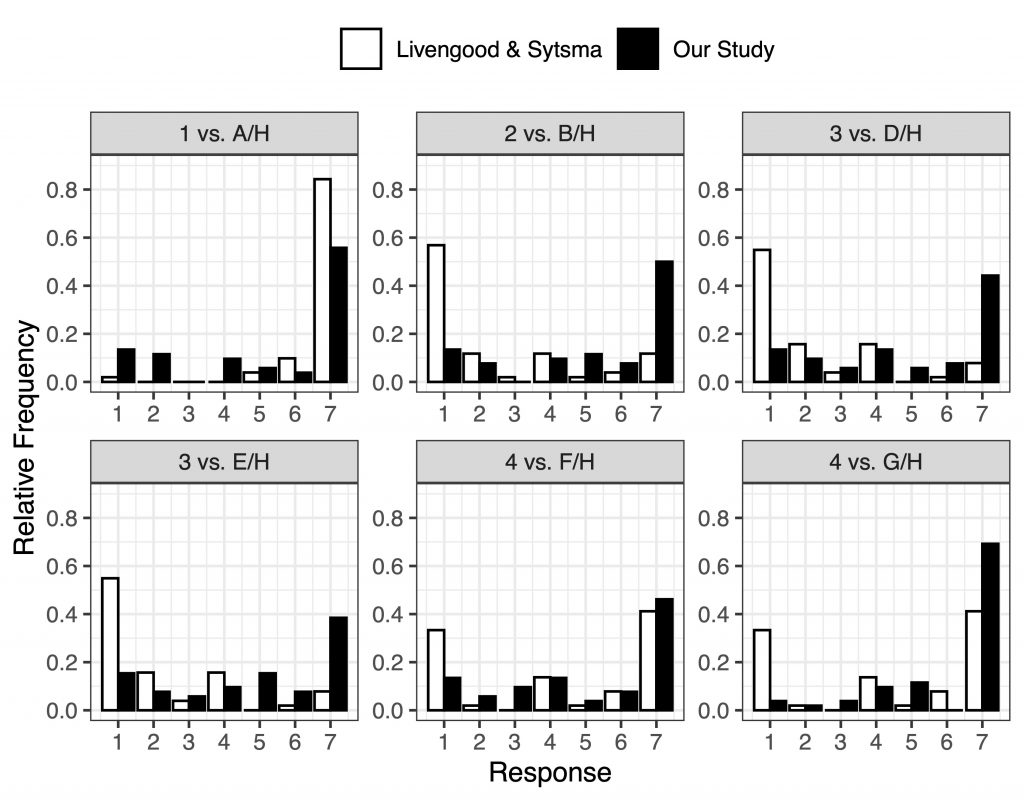

52 non-native English speakers completed the survey. And here comes the second twist: This time (and in stark contrast to Jonathan’s and Justin’s data), an (oftentimes overwhelming) majority of subjects chose to “strongly agree” that “X caused Y” for every item, including those that are analogues to the four statements from Jonathan’s and Justin’s study, as can be seen in the Figure below.

White bars represent data from Jonathan and Justin (1 = “Trent caused Brad’s death”, 2 = “The hammer caused Brad’s death”, 3 = “The gun powder caused Brad’s death”, 4 = “The bullet caused Brad’s death”), black bars represent our data (A/H = “Pull- ing the trigger caused the death of Brad”, B/H = “Releasing the hammer caused the death of Brad”, D/H = “Igniting the gun powder caused the death of Brad”, E/H = “The explosion of the gun powder caused the death of Brad”, F/H = “The bullet being driven from the gun caused the death of Brad”, G/H = “The bullet hitting Brad in the head caused the death of Brad”). We assume that cases 1 and A/H, 2 and B/H, 3 and D/H, 3 and E/H, 4 and F/H, as well as 4 and G/H are analogous.

Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests (with p-values corrected) reject the hypothesis that the central tendency for any of the 28 combinations is smaller than or equal to the “neutral” answer of 4 on the scale.

I think that, first and foremost, this teaches us that when questioning people, we must be very careful not only in choosing our words but also in choosing our set of questions. The story they tell us, it seems, depends not only on our question’s wording but also on the catalogue of questions that we put together in the first place.

This study, I’m afraid, doesn’t tell us anything about the origin of this difference yet. This clearly must be addressed in future research. To be honest, I am not even sure what – of all the available attempts – might be the best (or my favourite) explanation.

Jonathan and Justin state that “even philosophers, such as Lewis and Menzies, explicitly giving analyses of the ordinary concept of causation have offered theories that entail the compositionality constraint”. They ask: “How could they have gotten things so wrong?” (Livengood and Sytsma 2020, 64f.) What I am sure about, now, is this: Their conclusion seems a bit hasty.

Our small study has been published as a discussion note in Philosophy of Science. You can find it here. And stay tuned: Of course, a more fleshed-out study – first reproducing the findings from Justin and Jonathan for their different vignettes and then applying various variations of the task – is already on its way!

Literature

Bauer, Alexander Max, and Jan Romann (2022): “Answers at Gunpoint. On Livengood and Sytsma’s Revolver Case”. Philosophy of Science 89 (1), 180–192. (Link)

Livengood, Jonathan, and Justin Sytsma (2020): “Actual Causation and Compositionality”. Philosophy of Science 87 (1), 43–69. (Link)

Livengood, Jonathan, Justin Sytsma, and David Rose (2019): “Following the FAD. Folk Attributions and Theories of Actual Causation”. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 8, 273–294. (Link)